The expeditions of HMS Beagle (1831-36) and Tara Oceans (2009-12). Charles Darwin and Capt Robert Fitzroy.

His Majesty’s Ship Beagle is among the most celebrated of all British warships, commissioned in 1820 as a Cherokee Class, 10-gun brig-sloop. I always thought that it was odd to name a ship after a dog, unless of course there was an actual Mr. or Mrs. Beagle around back then who was worthy of such a recognition. But I could not find anything about how the name was selected other than that it was named after a breed of dog. The other warship captains must have had a fun time teasing the first captain of the Beagle. Can anyone tell me a famous (or even not so famous) American or French ship named after a dog? Considering how the English (and the Irish too) name their pubs– Pig & Whistle, as an example—it maybe not be altogether outside the realm of imagination for the British to choose a dog.

Why choose the beagle for a warship’s “nom de guerre?” That’s hardly the kind of name that instills a sense of awe, power and danger. The beagle is generally described as even tempered, merry, amiable, non-aggressive and poor guard dogs. The word beagle has many possible origins, but I like to think it came from the Gaelic word beag, meaning little. The only reason I can find, from reading about beagles, was that the beagle, as we now know as a breed, was developed in Great Britain about the same period when the ship was commissioned. The beagle was so well liked that it had been depicted in art and written in the popular literature long before the commissioning of the ship, as far back as the Elizabethan period. Even in this century, the British named its Mars landing spacecraft, Beagle 2, in honor of HMS Beagle. Or, maybe they just have yet to outgrow their fondness of beagles. Guess who is the most popular dog in the whole wide world? Snoopy. And, he’s a beagle, of course. So now you know!

I am digressing from the important topic of the day, but I can’t help but finally settle this nagging question in my mind (and yours too I’m sure).

Now back to some science.

In the previous blog entry on Charles Darwin, I briefly mentioned the ship. I think it is time to at least take a moment to devote some thoughts about HMS Beagle. After the fanfare of being the first ship of the line to cross the new London Bridge in celebration of the coronation of King George IV, the ship remained moored until later when it took part in three survey expeditions. The Beagle itself was not a highly regarded ship of the line by its sailors who referred to it as a “coffin brig”–more likely to sink to the bottom than sail around the world. The duties of the first survey were so lonely and yet so stressful that its first commander, Lieutenant Pringle Stokes, committed suicide in Cape Horn. On the second voyage, Stoke’s nephew, Lieutenant Robert Fitzroy was appointed captain. In this forthcoming second voyage, Captain Fitzroy needed to avoid the same fate as his uncle by cleverly bringing in a paying passenger-naturalist who would conduct the surveys of the land so that the ship’s officers may attend to the more important military task of ‘hydrography.” This young man, Charles Darwin, on his way to becoming a clergyman, became that naturalist. And the rest is history.

HMS Beagle

On this second voyage, initially planned as a three year survey that became five years (1831-1836), HMS Beagle circumnavigated South America and then the globe. It was a magnificent feat of seamanship, using 22 chronometers and with only 33 seconds of error. Though largely forgotten, HMS Beagle also had its place in world history. It was one of the three ships that helped the British take the Falklands Islands from Argentina in 1883, eventually leading to the Falklands War between the two countries a hundred years later. The Beagle Channel and the Beagle Islands of Tiera del Fuego, in South America’s southernmost tip, representing one of the three gateways to the Pacific, were named after this ship. Conflicting claims to those islands also almost led to a war between Argentina and Chile in 1904. Aptly named the Beagle Conflict, this arose because of Argentinean claims to the islands and Chile’s refusal to accede. It took mediation by the Vatican to resolve this issue 80 years later. Argentina accepted the papal decree of 1984 making the Beagle Islands and the Beagle Channel as territories of Chile.

Yet, history barely remembers the Beagle and its captain. Instead, history took note of the Beagle’s paying passenger and would-be clergyman whose ideas, formed during this voyage, became the foundation of our understanding of the diversity of life on earth.

The tale does not end there. One of Darwin’s most ardent detractors and one of the champions of anti-evolution crusade turned out to be none other HMS Beagle’s own Captain Fitzroy. Their opinions of each other, though strained during the voyage, diverged dramatically long after the expedition. It is ironic that the aspiring clergyman came up with the idea of evolution that shook the foundations of the Church teachings, while the military man, duty bound to vanquish all enemies of the Crown, became one of the Church’s most vocal champions.

Tara Oceans

Scientific expeditions, whether on land or at sea, always have a romantic appeal. Expeditions meant adventure and excitement. One can only imagine the thrill and the foreboding that Darwin felt as he embarked on this naturalists’ dream of exploration. That same sense of adventure, despite all the sophistication and the trappings of our modern digitally enhanced world, still remains today.

The marine ecosystem is still poorly understood; we only see bits and pieces of it. But each ecosystem is not isolated but part of a larger system; each part impacting the whole. Within that complexity is the diversity of life, interacting often in unique and often unfathomable ways.

Despite mankind’s technological prowess, it is not an easy task to understand this complexity. To solve this puzzle, we do need to start at the bottom, the very basic life forms of each ecosystem and somehow integrate this into the wider knowledge of our planet’s water world. What can be more basic that the bacteria, zooplanktons, phytoplanktons, microalgae and viruses that make up 30% of the primary biomass of the ocean and the source of 95% of the respiration of our planet. This is what makes Tara Expeditions a unique, singular maritime adventure of our time.

Tara Oceans is a specially designed 118 ft. aluminum schooner, sponsored by the French Center for Scientific Research (CNRS), the European Molecular Biology Laboratory (EMBL) and many other marine research institutions. Its principal partnerships include the United Nations Environmental (UNEP) program and the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). Its main purpose is to conduct surveys of marine ecosystems as it travels on its 3-year voyage around the world. Tara Oceans has a 5-man crew and room for 7 scientists. Their task is to examine marine plankton and other microbial life in the oceans and near coral reefs as it travels along its 100,000-mile route.

Tara Expeditions started in 2003 because of the vision of its patron, Agnes B, founder of one of France’s most prominent fashion brand, Agnes b. Her dream was to understand and make a significant contribution to mitigating the effects of the warming oceans. Since the acquisition of the schooner, Tara, that vision has already taken the ship and its research teams through 7 expeditions in the Arctic, Antarctic and the seas around Patagonia and South Georgia.

In 2009 (coincidentally the 200th anniversary of Darwin’s birth and 150th anniversary of the publication of the Origins of Species) Tara Oceans embarked on this new 3-year odyssey to study the basic life forms that drive the diversity and productivity of our oceans. As a moving platform, complete with sophisticated imaging and biological research facilities, Tara Oceans brings together an international team of scientists to conduct over 20 major projects. Today, Tara Oceans is in the island of Mayotte in the Indian Ocean on a coral research project, prior to sailing to Cape Town, South Africa.

While there is not enough room in this article to talk about all the research programs during this expedition, it might be of interest to just mention a few to give you the flavor and the sophistication of this voyage. TANIT (TAra OceaNs ProkaryiotIc FuncTioning and Diversity) is a consortium of scientists investigating the functioning ecology and biodiversity of bacteria in the oceans. Virus hunters from the Université de la Méditerranée (Marseille, France) shall examine the genome of the MimiVirus, the largest known virus, from the group of giant viruses, called Giruses, which infect a wide range of marine life forms. The hunt for new ocean viruses will provide a better understanding not only of the genetic diversity but also the role these organisms play in the overall health of the oceans. The Tara Oceans Marine Biology Imaging platform (TAOMI) integrates all of the data from the research teams as a “tool to extract functional correlations between genes, the diversity of organisms present in a given region and the physical environment.”

How does Tara Oceans manage to attract such a wide range of scientists from the world’s premier institutions? That I don’t know. But, just to impress you, here is the array of acronyms of all the scientific organizations involved:

CNRS / ENS, Paris, France; NOC, Southampton, UK; CNRS/UPMC, Paris, Roscoff, Banyuls, Villefranche-sur-Mer, France; Stazione Zoologica, Naples, Italy ; Marine Biology Laboratory, Woods Hole, USA ; Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Boston, USA; University of Washington, Seattle, USA; University of California, Santa Cruz, USA; Flinders University, Adelaïde, Australia; JAMSTEC, Kanagawa, Japan; ICM-CSIC, Spain; Bigelow Laboratory, USA; CNRS/IMM /IGS, CNRS /OOB, CNRS / UPMC, Paris, Villefranche-sur-Mer, France; Centre Scientifique de Monaco University of Milan, Bicocca, Italy; MNHN, Paris France; James Cook University, Townsville, Australia; Museum of Tropical Queensland, Townsville, Australia ; CORDIO East Africa, Mombasa, Kenya ; University of Warwick, Coventry, UK ; Nova Southeastern University, Florida, USA; Tara Expeditions, Paris, France; University of Maine, Orono, USA; ACRI-ST, Sofia-Antipolis, France; LEGOS/CNRS, Toulouse, France; GIP Mercator Océan/CNRS, Ramonville St Agne, France; METEO France, Toulouse, France; Satlantic Inc., Halifax, Canada; Hydroptic Ltd., Lisle en Dodon, France; WDC-MARE/PANGAEA®, Bremen, Germany; IFREMER, Brest, France; University of Hawaii, USA; LOG, Wimereux, France; EMBL, Heidelberg, Germany; University of Washington, Seattle, USA; Genoscope, Evry, France; EBI, Cambridge, UK ; IOBIS/Cmarz/Census of Marine Life, Washington, USA.

And, as of June 17, 2010, the newest member of the team—Poseidon Sciences!

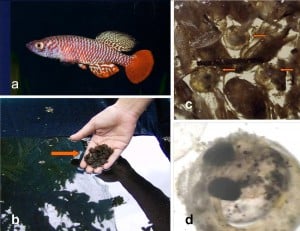

I am sure you are dying to know why we are part of this. In my previous blog entry on Darwin, I wrote about Darwin’s 8-year passion to classify barnacles. Unfortunately, I caught the same, perhaps nastier ‘bug’ and now on my 15th year of the same obsession. This time, there is an urgent concern by environmentalist and the maritime industry about invasive species carried by ships on their submerged hulls. Because Tara Oceans will sail to various oceanic environments and stop at different ports of call, it is now possible to critically examine what kinds of biological hitchhikers are present in different regions, how long they remain attached and the succession of different biofouling attachments as the ship sails through different waters. This is an unprecedented opportunity to look at this issue, with marine biologists on board, supported by Poseidon Sciences’ marine research stations around the world. Tara’s TAOMI system will integrate the data and enable a continuous look at the biological processes at play on a ship traversing all the oceans.

To make this program meaningful to the maritime industry, the Tara-Poseidon program shall encourage industry participation by enabling marine coatings companies to paint 1 m2 patches on the underside of the hull to measure the performance of their coatings against fouling attachments while comparing those results with uncoated patches along the hull. There has been a proliferation of coatings with claims of performance against fouling attachments in the absence of TBT (tributyl tin, a toxin outlawed by the International Maritime Organization of the United Nations) and copper. This is a unique opportunity to validate the performance of such systems (copper-free and low copper) under the challenging conditions of Tara’s expeditions.

There is one similarity between HMS Beagle and Tara Oceans. Both ships are the tools to answer questions relevant to people of their time. The Beagle’s mission of hydrology was crucial to maintain the British dominance of the high seas during the 19th century. Tara Ocean’s mission, likewise among the most important of our time, 178 years later, is to understand the organisms that are crucial to support the diversity of life in our oceans and sustain the atmosphere on earth. And, from that gained knowledge, find ways to plan for its remediation, as the founder, Ages B, had envisioned.

As in most scientific expeditions, it is the chance of discovery that fuels the excitement. In the case of Charles Darwin, his ideas on evolution might not have formed without the convergence of Darwin and HMS Beagle at that point in human history.

As Tara Oceans sail through the deep blue sea–who knows. Among us might be the next human being that could be the instrument of change in the ocean’s future.

Welcome aboard!

Jonathan R. Matias

Poseidon Sciences

June 28, 2010 New York, USA

PS: Just a little more about Captain Robert Fitzroy, the forgotten pioneer

After the Beagle expeditions, Fitzroy made it possible for weather observation equipment to be available in every ship in English ports. This accomplishment and his precise hydrological charts had saved countless sailors from heavy storms. The first scientific weather forecasting station was devised by Fitzroy, using the telegraph as the method to transmit data from far flung weather stations. Despite the publication of his Weather Book in 1862, which became the inspiration for the very first daily weather forecast in the Times of London, he received little fame. In poor health, depression from lack of recognition and losing the fight against Darwin’s evolutionary theory, Captain Fitzroy went the way of the previous captain of the Beagle. He committed suicide in 1865. It is only recently that the British government and the world’s atmospheric scientists recognize the pioneering work of Captain Robert Fitzroy in weather forecasting.

The object lesson: Be nice to the captain of Tara Oceans. He has a lot to worry about.

For further reading:

About the Beagle

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Beagle

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Beagle_2

The Tara Oceans scientific program

http://oceans.taraexpeditions.org/en/the-expedition/the-expedition.php?id_page=24

Poseidon Sciences