A black man was killed a few days ago. No, it’s not gang violence. It’s neither drug related nor a party in the ‘housing projects’ gone out of hand. It’s not an accidental shooting or from a robbery gone astray. Nor was it even a traffic accident. Most people would have said that he had died or simply passed away, but I say he was killed. The word ‘dying’ seems to sound so natural, so passive, as if his death was an expected, common place event. He was killed by something even more sinister, more insidious, more violent and even more heartbreaking. He was killed by his own cells, his very own DNA, aberrant as it might be, but it is his own nonetheless. He was killed by prostate cancer. And he was my friend. His name: Dr. Lloyd A. Williams, neurosurgeon.

I meant to write about cancer research much later on, but his death brings this subject much closer to home. He was an unassuming man for a neurosurgeon, mild-mannered, soft-spoken, cultured and full of wonderful dreams. On warm summer’s evenings, he would come by my home for a short visit and we would sit near the backyard fish pond watching Japanese carps swim by. Surrounded by tall flowering night jasmines and bamboo trees, he would relax finally on those rare days when he was not working as the neurosurgeon at the two local hospitals. We talked about science, his love of philosophy, the old books he has been collecting and his dreams of writing poetry when he can finally relax from the miseries of doing surgery 6 days a week. He was ambitious, holding two jobs to generate enough wealth to fulfill his dreams. An immigrant from Jamaica finally attaining the great American dream—a grand home, investment properties, a wife, a kid. He talked about his parents and how their old dreams for him finally materializing. I told him that there is so much coincidence here; a Jamaican immigrant living in Jamaica Estates, NY, drinking Jamaican rum. He just laughed. We instantly found some common interests the first time we met and I had enjoyed those rare visits year after year. The pond was our “happy place” to unwind, feel the breeze, and settle for a spell, just enjoying a cognac or two by the side of a little campfire.

I meant to write about cancer research much later on, but his death brings this subject much closer to home. He was an unassuming man for a neurosurgeon, mild-mannered, soft-spoken, cultured and full of wonderful dreams. On warm summer’s evenings, he would come by my home for a short visit and we would sit near the backyard fish pond watching Japanese carps swim by. Surrounded by tall flowering night jasmines and bamboo trees, he would relax finally on those rare days when he was not working as the neurosurgeon at the two local hospitals. We talked about science, his love of philosophy, the old books he has been collecting and his dreams of writing poetry when he can finally relax from the miseries of doing surgery 6 days a week. He was ambitious, holding two jobs to generate enough wealth to fulfill his dreams. An immigrant from Jamaica finally attaining the great American dream—a grand home, investment properties, a wife, a kid. He talked about his parents and how their old dreams for him finally materializing. I told him that there is so much coincidence here; a Jamaican immigrant living in Jamaica Estates, NY, drinking Jamaican rum. He just laughed. We instantly found some common interests the first time we met and I had enjoyed those rare visits year after year. The pond was our “happy place” to unwind, feel the breeze, and settle for a spell, just enjoying a cognac or two by the side of a little campfire.

In the summer of 2009, he looked more subdued than usual. He told me that he has inoperable late stage adenocarcinoma of the prostate that has already metastasized to the liver and pelvic bone. I did not know what to say, but the first thing that entered my mind was how can an M.D. miss the early warning signs and let cancer get this far. The second thought was the misery I had seen when another person I knew long ago died from metastatic lung cancer. Then, I thought of my father-in-law who died from prostate cancer too. The pain and suffering for both him and his family were about to come and I can’t do anything about it at all.

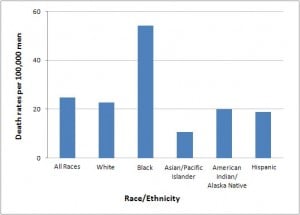

He was an energetic, seemingly healthy man. The cancer was not detectable until the pain started. Statistics say that 1 out of 6 men will get prostate cancer and African-Americans have more than twice as much probability of getting it than the rest of the male population in the United States. I knew all of that. I did research on prostate cancer for a few years, although in a rat model of adenocarcinoma. I have followed the scientific literature over the years. But, what can I do for him?

US mortality rate for prostate cancer (2003-2007) according to ethnicity. Data derived from: SEER,National Cancer Institute, NIH

There’s hardly anything out there for late stage prostate adenocarcinoma. But, there is always hope and there is the never ending stream of scientific papers each week about cancer. Perhaps, there might be some clue, maybe too novel as yet, that might give us some rays of hope. So, we agreed that I will read the literature more closely and will mail him a copy of each paper that I thought would be useful. And so started my odyssey of reading prostate cancer papers each week. It became almost a ritual, with my secretary printing the latest articles of the week and mailing him a copy, a weekly routine that has gone on for over a year.

I had not seen him since that summer evening, though we talked on the phone. He was fighting the cancer, traveling to different hospitals, more surgeries, more pain and more hope. He could barely read the articles I sent him. But, he fought this disease with such overwhelming tenacity like a gladiator in combat. He gave a good fight.

Last Friday, October 1st, I felt the end was near. I thought of going to his home anyway, just half a mile away from mine. But I did not. He died at 5:00 PM that same day. I have the same guilty feelings that many of us lucky enough not to have cancer–yet. They are the same emotions felt by those who survived a natural disaster or a soldier surviving a firefight in some godforsaken corner of the world while other friends did not.

Having read, scanned, and browsed all of the recent literature on prostate cancer till I was worn out seemed like a hopeless exercise in futility now. Yes, so much is known about the biology of cancer. Much progress has been made. But the progress made were not big leaps forward, not even mini-jumps. They are all micro-steps, each of those steps cost a lot, not in terms of just money, but intellectual energy because cancer researchers are among the most passionate, determined scientists I know.

To give you an idea how much has been written about it; just go search ‘prostate cancer’ at PubMed, a database comprising over 20 million citations of medical literature by the US National Library of Medicine, National Institute of Health. From Sept. 1, 2010 till October 1, 2010 there were 400+ scientific papers on the subject in this short span of time. The very first paper in that database was by Dr. C. E. Liesching, printed in 1894 in the British Medical Journal. And, 768 more followed by the end of the year — 89,105 scientific papers in all from 1894 till Oct.1, 2010. That’s just what has been indexed, not counting articles and other journals not included in PubMed. If you think that’s a lot on just one subject, here’s another one for you. Breast cancer papers was included in PubMed starting from the 1868 article by Dr. Thomas Bryant, also in the British Medical Journal, to a total of 219,395 papers until October 1. Three times more papers on breasts than on prostates. Can’t say I blame the researchers, who predominantly were mostly male. Even if I just take an arbitrary average length of each paper as 3 pages each, this translates to 925,500 pages when you combine the two topics, almost a million pages of ideas.

Then, you may ask, “Where are we now after almost 1 million pages of print and untold billions (or trillions of dollars)?” The answer would be different for a scientist and for a lay person. From the scientific point of view, we have made great strides in the treatments, prevention, the understanding of the mechanisms from the sub-molecular, molecular, cellular, organ and whole animal levels. We achieved great successes in palliative care, new instrumentations to monitor the growth and development, of detection, new anticancer drugs, etc… The list is quite long when you consider the incremental scientific advances. For the lay person who simply wants to know if we have the means to cure or even a definitive means to prevent, then the answer would be more disappointing—we are still quite far away. If one looks at it from a historical analogy we are still in the Renaissance Period. Certainly we have overcome the Dark Ages and chasing fervently for answers. We have yet to reach Enlightenment and many more, like Dr Williams, will fall victim till we do.

We have sent spaceships to the distant planets and beyond. We have sent submersibles to the deepest depths of the oceans. Why is the cancer problem so difficult, you may ask? The answer is because it’s a biological phenomenon, not a physical one where all the variables are predictable and easily quantifiable. The cancer cell is a tough opponent—it mutates, it can develop resistance to drugs, it can grow faster than most normal cells, it can hide inside tissues, it can travel at will, it can lie dormant and it can make the blood vessels migrate to it to keep supplying its growing needs. If there is an equivalent of a Superman in cells, the cancer cell is it!

I have no answers either and can only offer a philosophical view why it is this way. The cancer cell is a cryptic enemy. It hides in plain sight. It blends with the environment. And it is not a foreign body that exhibits flamboyant markers to separate it from the rest of your cells. It is one of your own, just behaving badly by nature or by other unknown external factors that stimulated it. In many ways, the cancer cell is parasitic, like the parasitic wasp that lay eggs on other insect larvae. The newly hatched wasps consuming the victim till they emerged out of the victim’s body, like the monster in the movie “Alien.” Yet, it is not quite all that either. Cancer grows within our tissues, taking the cellular machineries of the host to propagate itself to the point that it kills the host and itself in the process. It is also like a virus, infecting the cells, dividing to create new viruses, rupturing the cells to invade more cells. Like cancer, the virus hides from the immune response by masking itself, pretending it is part of the body. There are many biological analogies I can recite that explain cancer more, but always there are exceptions. No living organisms, even plants, escape the presence of cancerous growth. Sharks, once thought to be immune from it, is now found to also have them. It is just that sick sharks simply get eaten by their fellow sharks so that sick animals are rarely detected.

Fighting cancer is like fighting a war in human scale, not the traditional, conventional, symmetrical one where you know who the enemy is and where they generally are. This cancer fight is a pure asymmetric warfare, a guerilla action against the state, a conflict between two belligerents exploiting each other’s characteristic weaknesses using strategies and tactics in unconventional ways. The enemy hides within the population of innocents, yet co-opting the innocents to do their bidding to support its own survival. The guerilla is part of the society, just an aberrant part, with different ideologies, but looks like everyone else. The guerilla mutates into different forms to avoid surveillance, changes tactics to adjust to situations. The larger force trying to maintain control expends massive efforts, materiel and fighting elements to keep the guerillas in check, catching a few out in the open, but missing many that blends well with their environment. They lay dormant when times are bad. They recruit new members to replace the lost ones and wait for the right time to strike back at the government’s weakest point or weakest moments. The cycle of attrition goes on indefinitely at times, sapping the strength of the presumably stronger force little by little. This cancer war is no different than Afghanistan, Iraq, Vietnam and others like it.

The only difference is that cancer has no ideology that we understand in human terms. No single purpose other than the survival of its own kind. No plans to invade other bodies outside of the confines of the single human host. No aspirations and none of the awareness that the death of the host equals its own death as well.

How do we win this war? Certainly not through the current dogma we are following now. The successes are incremental and easily reversed by unforeseen events, like drug resistance and mutations of the cancer cells to evade immune surveillance. It is certainly not going to be won by drugs that simply give 4 months of life extension at best for the value of $93,000 as in Provenge. It can only be won by asymmetric thinking, with by new ideas out of the mainstream, out- of- the- box. But such a war against cancer has to be a determined one, fueled not by massive amounts of money directed at everything else under the sun, but a targeted approach using a new tactic never before taken. We have enough understanding of what makes a cancer cell unique, what we are lacking is a coordinated strategy, action and purpose. Asymmetric or not, let’s treat this like a real war, not the symbolic names politicians use. Let’s fight it the way we won World War II, with both industry and government in synchrony to bring all its massive forces to bear on a single purpose of destroying cancer by targeted means. It will not be won by simply nit-picking and aimless meandering in broad fronts the way we are pursuing it now.

The last sentences in Thomas Bryant’s 1896 article seem apropos:

It is true that what I have stated is not new….. If the cases I have brought forward have any influence in reminding us of what we have sometimes neglected, or in urging us to do what we cannot fail to recognize to be right, my object will have been obtained; for in our profession, as in many others, the old saying is too true, “That more error is wrought by want of thought, by far, than want of brains.”

Success in a scientific endeavor comes on the heels of the mini-successes that others had made long before. I think we have learned so much in the last decade alone and it’s time to somehow integrate these into a more meaningful course of action. Perhaps, in the not so distant future, we can save another Lloyd Williams from being killed by cancer in the midst of fulfilling his dreams.

Jonathan R. Matias, Chief Technology Officer

Poseidon Sciences Group, New York, NY

Additional reading

http://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/prost.html

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/

Liesching CE (1894) Br Med J., 1(1745):1241. htttp://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2405244/pdf/brmedj08955-0009b.pdf

Bryant T (1868) Br Med J., 2(415):608-609.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2311200/pdf/brmedj05591-0002.pdf

This article is dedicated to:

DR. LLOYD A. WILLIAMS

a neurosurgeon and a dreamer who loved science, medicine, music, philosophy and most of all, his family