Native Americans (such as the Pomo, the Ge, the Serrano and Hupa), the Vikings and the Chinese all have their own myths about the lunar eclipse. The Vikings believed that the moon is eaten by Hati, the wolf; the ancient Chinese says that the dragon ate the moon; the Serrano Indians thought that the dead spirits did it too. There are two common themes—that something ate the moon and it takes loud noises to make these things give it up. For the Chinese, the moon is represented by the mirror and during the lunar eclipse, millions of Chinese beat mirrors to make the dragon give back the moon.

Native Americans (such as the Pomo, the Ge, the Serrano and Hupa), the Vikings and the Chinese all have their own myths about the lunar eclipse. The Vikings believed that the moon is eaten by Hati, the wolf; the ancient Chinese says that the dragon ate the moon; the Serrano Indians thought that the dead spirits did it too. There are two common themes—that something ate the moon and it takes loud noises to make these things give it up. For the Chinese, the moon is represented by the mirror and during the lunar eclipse, millions of Chinese beat mirrors to make the dragon give back the moon.

My lunar eclipse experience did not involve making a lot of noise, though I can hear my teeth chattering from the cold. After all it was after midnight in New York City and my neighbors might call the cops on me if I started beating mirrors. I suppose New Yorkers are not ancient enough yet to develop lunar myths and, if we ever do, it is not likely to involve making loud noises. Maybe a sudden rush to Starbucks for the new ‘moon latte’ is more like it. I was among the perhaps 1.5 billion people on Earth that watched the lunar eclipse unfold last Tuesday, December 21, 2010. I seem to have been the only crazy one in my neighborhood to stay through that 3 hours and 38 minutes outdoor viewing event at 30 oF. But, I had to see it.

Though lunar eclipses are reasonably common, this one is particularly rare because it comes at the precise time of the solstice. For those like me who are unfamiliar with the term, solstice (from Latin sol meaning ‘sun’ and sistere meaning ‘to stand still’) occurs when the Sun’s apparent position in the sky from an earthbound observer reaches its northernmost or southernmost extremes at which time the movement of the sun comes to a stop before reversing direction towards north or south. I am sure you are still a bit confused by this explanation, but the story must go on !

I was told that the previous eclipse occurring at the same time as the solstice was in 1638 and the next one won’t come till 2094. Unless someone discovered Ponce de Leon’s ‘Fountain of Youth” or some scientist finally figure out how to stop aging, I don’t think I will make it to the next moon show. Even if I did, I will probably be just as happy to be breathing and the last thing I would want is to be outdoors at 30 oF ever again watching the moon turn red.

As I was thinking of tropical themes to keep my mind off the morning freeze (for instance–sunset by a tropical beach, sipping margaritas at 85 oF under the coconut tree and attended to by exotic young maidens wearing a sarong), I remembered reading before about Christopher Columbus being marooned on his fourth voyage to the Caribbean, spending a year under coconut trees and warm beach of Jamaica, watching the lunar eclipse too—exactly how I would have wanted it. His lunar encounter was at least more interesting as you will read later on—so don’t go away. Finally getting my dose of astronomical adventures for the year, I went back inside to read more about the voyages of Columbus—and that’s because there was nothing good on TV at 4:30 AM for insomniacs like me.

So how the voyage of Columbus relates to the eclipse and Teredo worms? Science and history always converge at some point, often in unpredictable ways, sometimes taking me along for the ride as well. And, before I tell you about it, I think you need a short course on Teredo first.

The terrible Teredo, termites of the sea

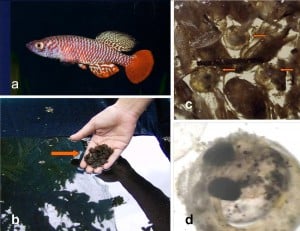

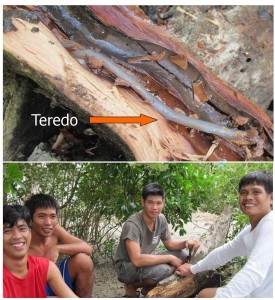

Teredo worms inside an infested wood being collected in Batan, Aklan Province, Philippines. Photos by Coleen P. Sucgang.

Anything that’s long, slimy and ugly is always termed a worm (as long as it doesn’t bite, which would automatically get the label as a snake) . However, this doesn’t apply to shipworms, also called by mariners as the ‘termites of the sea.’ Scientifically, they belong to the genus called Teredo, the most notorious of which is Teredo navalis, originally native to the Caribbean Sea. It is actually a clam, though looking at the pictures here, one would hardly believe that. But it is! And the male Teredo is one lucky stud. There’s 1 Teredo male per 1,500 females. Must be one very exhausted male and probably don’t live very long. For the male Teredo, this phrase certainly applies: “….live fast, die young and leave a beautiful corpse behind.” Just in case you are curious where it came from, the phrase originated from the 1947 novel by Willard Mothley about juvenile delinquents (turned into a 1949 movie with Humphrey Bogart) entitled “Knock on Any Door” and also often quoted lately to describe rock and movie stars dying young from drug overdose.

After fertilizing the eggs by the overworked (and maybe overjoyed) male Teredo, the developing eggs are protected inside the female until they develop into free swimming larvae. Then, the little terrors meander in the high saline sea until they find fresh wood (They don’t like old wood) to settle on, unless

A Teredo worm taken out of the wood and close-up images of the tri-lobed shell and siphons. Photo credit: Coleen P. Sucgang, Poseidon Sciences.

they get eaten first by something else. Then it starts burrowing through the wood as it grows, parallel to the grain, only turning to avoid any knot on the wood or if there is any obstruction. By the time it reaches adulthood, it is already at least a foot long and half inch thick. If you think this is big for a worm, its Sumatran cousin, the Giant Teredo, grows to six feet long, but lives in the muddy bottom of the sea rather than inside wood. Unlike other typical clams, the shell covers only a tiny portion of the Teredo and used more like a drill bit to burrow a circular hole through the wood. The tube-like home is capped at the opening of the burrow with a secreted calcareous cover, with protruding siphons that allow the animal to breathe, feed on plankton and excrete wastes. Inside its burrow, the Teredo‘s color is pinkish white. When removed out of its home, the color changes to a lighter blue shade in just a few minutes.

The good things about Teredo

Before I tell you the bad reputation of shipworms, it is only fair to describe a few good things about them.

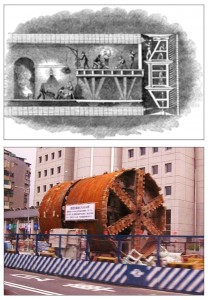

First, the tunneling behavior of the shipworm inspired Marc Brunel, a French engineer, to devise a method, which he patented in 1818, to tunnel under the Thames River in England, the first of its kind ever built under a muddy river bed. His technique called the “tunneling shield” made use of his observations while working on a shipyard on how the shell with fine ridges were used by the Teredo to drill through the wood while protecting itself from being crushed. The Teredo also secretes a calcium-rich framework that coated the inside surface of the tunnel, keeping it stable and crush proof.

Second, the cellulose that makes up the wood is not sufficiently nutritious as food and the shipworm cannot normally digest it. It overcomes this limitation through a symbiotic relationship with bacteria, Teredinibacter turnerae, in its gills that secrete enzymes, called cellulases and nitrogenases, breaking down the cellulose and fixing nitrogen to build amino acids. By the way, cellulases are the same enzymes, derived from fungi, used to create your stonewashed denim jeans by breaking down the cellulose on the outer surface of the cloth. Now, it is also a major ingredient in most laundry detergents to improve cleaning efficiency. The potential of Teredo-derived cellulases is in its future use in biofuels because it is likely more efficient than fungal cellulases in converting paper-mill cellulose waste into ethanol or methanol.

Third, Teredo worms serve an ecological purpose by degrading the wood materials that end up in the ocean.

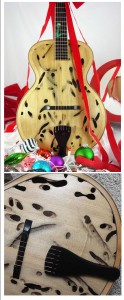

Benedetto archtop guitar made from Sitka spruce with Teredo holes. Bottom shows close-up of the guitar with the holes made by Teredo.

Fourth, Teredo-infested Alaskan Sitka spruce used as log floats back in the 1950’s and 60’s, when transformed into a 16” traditional Benedetto archtop guitar, becomes a unique, spectacular and most expensive archtop guitar at the hefty price of US$ 52,000.

And lastly, Teredo worms make a special Philippine delicacy called tamilok, appreciated only by natives of Palawan Island and Aklan Province in Panay Island. It is prepared raw as a ceviche or kinilaw in the local language, with vinegar, chili peppers and onions. Must be a scary delicacy and certainly not for the timid. Think of your appetizer as a moving, living, half-inch thick spaghetti. But, then again Teredo’s only known predators, the Palaweňos and the Aklanons, are probably more adventurous epicurian diners than the rest of us. I had been in both islands, had heard about it, but never did have a chance to sample this squirming dish. Maybe, I will try tamilok on my next trip down that way.

Tamilok: Teredo dish. Delicious, isn’t it?

My affair with Teredo

One of our long drawn out research project has been to develop a nontoxic repellent against a wide variety of invertebrates. Many years ago we have successfully developed one, called MR-08 that repels barnacles, mosquitoes, ants, flies, termites and even leeches. This is a food grade derivative of menthol with a propylene glycol side chain that reduced the menthol smell by 95% and increased the repellent effect many fold. So confident that it will work against Teredo, I asked our long time research collaborator, Sister Avelin Mary at Sacred Heart Marine Research Centre in India, to find areas with Teredo worms. We soaked fresh wood with MR-08 until we were confident that it has absorbed all the way into the wood and then immersed them for a few months in Tuticorin Bay in South India. No luck. Teredo just ate through that wood samples as if there was nothing there. So far, it is the only invertebrate organism that seems to have no reaction against our repellent.

I just gave up on MR-08 but I have a new idea for an ecofriendly, bioactive natural chemical that will prevent the Teredo from burrowing. So, just for the moment, Teredo wins the first round!

Now for the bad news

Shipworms have been a bane to ancient mariners until the advent of copper clad ships by the 18th century and modern marine coating on steel hulls. These boring clams weakened the wooden hulls of ships to the point that they break apart in the open sea without any warning. The Greeks and the Phoenicians certainly knew about them since 3,000 BC, lathering the hulls of their ships with wax and tar to keep them away. The Romans used combinations of lead, tar and pitch to cover their boat.

Unbeknownst to Columbus, his first voyage to the Caribbean Sea in 1492 exposed his ships to the world’s most Teredo-infested waters, likely due to the higher salinity and higher seawater temperature of the Caribbean. The ships that arrived later brought back Teredo navalis to Europe, where they can be found even as far away as the North Sea, having adapted to the cold environment. Hundreds of ships had been lost at sea just because of Teredo worms. These same worms caused the collapse of the wooden supports used in the dikes of Holland in 1731 causing flooding, 250 years after the first voyage of Columbus. Only the timely replacement of the outer surfaces of the dike with stones prevented more catastrophes.

In modern times, we have yet to escape the wrath of the Teredo. Wharves, piers, jetties and pilings started collapsing in San Francisco Bay between 1919 and 1921, resulting in almost 20 billion dollars worth of damage in today’s money, all because of Teredo. The mouth of the Hudson River of New Jersey and New York was once considered a ‘dead’ waterway, devoid of fish life because of the overwhelming industrial pollution since the 1930’s. Ship captains used to sail their boats through NY harbor just to kill off shipworms and barnacles. That’s how polluted it was. In 1972, the US Federal Clean Water Act limited discharge into the rivers and proactively revitalized the waterways. By the 1990’s fish had returned. And so did the Teredo, with a vengeance. During this period also saw the voluntary ban by the lumber industry on the use of creosote and CCA (chromated copper arsenate) to prevent further leaching of the toxic chromium and arsenic to the environment. These wood preservatives prevented fungi from rotting the wood away and also quite good at killing off termites and shipworms as well. These good deeds had unintended consequences—piers and piling along the Hudson River that no longer used preservatives started collapsing, hollowed through by Teredo worms.

Christopher Columbus

After discovering the New World by accident in 1492 (He was trying to reach India and China by going across the Atlantic), Columbus had undertaken three more voyages back to the Americas, mostly in search of riches in gold and silver to recover the cost of the previous voyages. But the Caribbean was not particularly rich in anything but warlike Caribs and Arawaks. Though forbidden by Queen Isabela of Spain to get involved in slave trading, financial pressures from investors forced Columbus to disobey. On his second voyage, he obtained 1,200 Arawak natives captured by the Carib tribe and transported 560 of them to Spain, 200 of whom died en route. Though the Spanish monarchs at the time disapproved of slavery, 200 of these natives were used as galley slaves nonetheless while the rest were returned back to their native lands. Though not widely known, Columbus’ second claim to fame is to start the slave trade in the New World.

In the province of Cicao in Hispaniola (now Haiti and Santo Domingo), to fulfill his promise to investors to fill his ship with gold, Columbus instituted a tribute system whereby each native above 14 years of age must pay in gold every 3 months. In return each received a copper token to be worn as a necklace (not quite a fair deal). Anyone caught without a copper token was punished by having their hands cut off. Though it failed to yield the riches he expected, that started the gold rush (his third accomplishment, if one can call it that) to the New World that destroyed the civilizations of the Incas, the Aztecs and the many other indigenous tribes in the Americas.

His fourth voyage was not particularly successful either. He went to Panama upon learning from the natives about more gold to be had and a strait connecting to another ocean. One of his ships was stranded in the river called Rio Belen and by the end of his voyage the garrison he built there was attacked; more ships damaged. More bad luck came on his way to Hispaniola in 1503 when a storm damaged his remaining flotilla and the hulls almost breached because of the Teredo worms that infested the wood. Most certainly, the ships would have broken apart had he went further. No choice but to beach his vessels in St. Ann’s Bay in Jamaica. Waiting for relief ships to come to his rescue, Columbus and his sailors had to rely on food and help from the natives who were momentarily awed by the presence of the new arrivals. As months go by, the natives got weary of the Columbus and his men. Angered by the occasional thievery and bad behavior of the sailors, the natives began refusing to send food to the point where his sailors wanted to invade the villages to take what they needed by force.

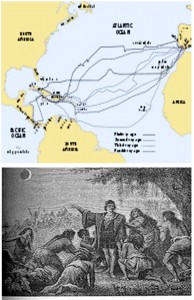

Map showing the four voyages of Christopher Columbus (top). Print with Columbus showing the natives that God is taking their moon away (bottom).

Columbus thought of a better way and summoned the village chiefs for a talk at sunset on February 29, 1504. Opening the discussion with the announcement that God was not pleased with the way the people were treating the sailors and that God would show his disapproval by taking the moon away were met with disbelief and laughter by the chiefs. No one controlled the sky as far as the natives were concerned. As the moon rose up in night sky, the bright full moon dimmed, lost half of its light. This loss of light continued until the moon dimmed completely, turning to amber color. The natives began to wail, begging Columbus to beseech the Almighty to return the moon. Frightened by the display of this ultimate celestial power, they promised to bring food once again to the sailors in return for forgiveness and giving the moon back to them.

Columbus told the chiefs that he would consult with the Almighty in his hut for a while to see if God is in a forgiving mood, likely just checking his hour glass and waiting for the right moment. Then Columbus returned after 48 minutes to declare that God had forgiven them and was returning the moon again. And God promptly did. Soon after his declaration, the lunar totality was completed and the bright moon reappeared once again. The lunar eclipse saved Columbus and his men from starvation and saved the villagers from rampage by the sailors.

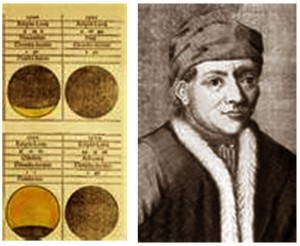

How did Columbus know about the lunar eclipse? He kept a copy of the Ephemeris by the great German astronomer, Regiomontanus, with him on his voyages.

The Ephemeris (from the Greek ephemerios meaning ‘daily’) is similar to what we consider now as the almanac. Johannes Müller von Königsberg (6 June 1436 – 6 July 1476), more widely known by his Latin name Regiomontanus (It was fashionable at the time for famous scholars to adopt Latin names), was a mathematician, an astronomer, translator of Ptolemy’s writing and famous for his astronomical tables and instruments (sundials, astrolabes) in the 15th century. A precocious boy, he went to the university in Leipzig at age of 11 and received his degree of ‘magister artium’ (Master of Arts) at 21 in Vienna in 1457. His astronomical and mathematical works were the best of his time and his Ephemeris considered one of the first applications of mechanical computers. A moon crater is even named after Regiomontanus.

The Ephemeris was a printed table of values that gives positions of the objects in the sky at any given time using a spherical polar coordinate system of right ascension and declination. Regiomontanus went to Vienna in 1475, a year before his death, to help Pope Sixtus IV to reform the calendar and along the way managed to finally print his Ephemeris, a copy of which was carried by Columbus two decades later on his voyages.

This story is truly a convergence of many unrelated events:

- Teredo worms destroying Columbus’ ships

- The total lunar eclipse happening while Columbus was stranded and his trouble with the natives

- Regiomontanus publishing the Ephemeris and Columbus having a copy with him on his voyages.

The voyages of Columbus were full of accidental discoveries and his survival on that last voyage showed that, despite his misfortunes as a ‘get-rich quick’ fellow, he was still a one very lucky seaman in the end.

And, the Teredo still reign as the world’s best little terror of the high seas. Who knows, 200 years from now the Teredo may even evolve to burrow through plastics, paint and steel. Then, we will be in real trouble!

Jonathan R. Matias, Chief Science Officer

Poseidon Sciences Group

www.poseidonsciences.com

Suggested Reading:

For interesting stories about the Teredo, please read the articles by Jerilee Wei and Kristin Cobb below:

Jerilee Wei. Teredo. The terrible shipworm that eats wood. http://hubpages.com/hub/Teredo-The-Terrible-Shipworm

Kristin Cobb, Science News, Aug. 3, 2002. Castaway: the gripping story of a boring clam – shipworm. http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m1200/is_5_162/ai_90468391/?tag=content;col1

http://www.poseidonsciences.com/MR08_nontoxic_repellent_menthol_mosquitoes_flies_termites.pdf

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shipworm

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Regiomontanus

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ephemeris

http://www.1911encyclopedia.org/Teredo

http://www.frammandearter.se/0/2english/pdf/Teredo_navalis.pdf