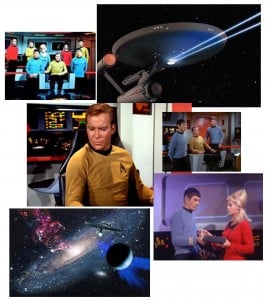

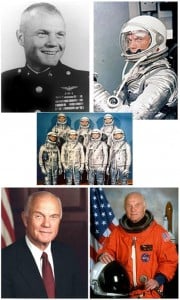

This seems such an odd topic from the start, but I thought it’s worth revisiting in celebration of today’s 50th anniversary of John Glenn’s orbital flight around the earth. John Glenn and Scott Carpenter (who will be celebrating his own 50th anniversary in May) are the last surviving members of the original seven astronauts of NASA’s Project Mercury. Though two other Russian cosmonauts had orbital flights before his, John Glenn’s flight was America’s first and its success changed the momentum of the race to the moon to America’s favor.

Looking back 50 years, I am always amazed at the significant advances mankind has made as a result of the space race with Soviet Russia — calculators, computers, internet, among many. Mankind seems to excel when in competition, whether at war, in commerce or in the arts. The rudimentary equipment half a century ago could not even compare with the precision of our digital age. Many of the technologies we now take for granted were pioneered by the men and women of Project Mercury. Those that followed in their wake made American pre-eminence in technology possible.

Looking back 50 years, I am always amazed at the significant advances mankind has made as a result of the space race with Soviet Russia — calculators, computers, internet, among many. Mankind seems to excel when in competition, whether at war, in commerce or in the arts. The rudimentary equipment half a century ago could not even compare with the precision of our digital age. Many of the technologies we now take for granted were pioneered by the men and women of Project Mercury. Those that followed in their wake made American pre-eminence in technology possible.

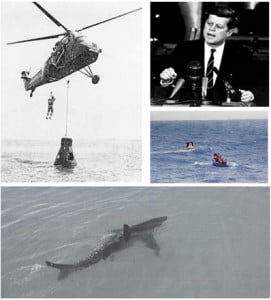

Space travel was a fascination for me long after the Mercury astronauts had made their mark in history. I was only aware of them through later documentaries. As a young boy in the 60’s, there was certainly the thrill of watching the spaceships blast off to space. Yet, I was more keenly interested in the splash down when the capsule plunges into the sea on its return trip. There was that unexplainable excitement at seeing the helicopters hover around the capsule to retrieve the astronaut and the tiny space capsule. What seemed odd at time were the other helicopters hovering around with sharpshooters on board. It wasn’t till later when I got interested in sharks that I learned why.

So, this is my “Shark’s Tale’ for you. And it’s not about saving the shark from extinction, who got bitten lately or about shark fin soup. Before I tell you the rest of the story, I would like to tell you a little bit more about shark repellents first.

Between sports fishing, by-catch from longline fishing and the Chinese penchant for shark’s fin soup, mankind has devastated the world’s shark population to the point that sharks are becoming endangered. But the fear of sharks remains with us. It is a visceral fear. More people die of bee stings than shark bites. With bears or lions, the fear is also there, but tempered by the fact that we can always carry a gun, can run off in a jeep or simply hide inside a house. With sharks the fear is magnified because there is really not much one can do in the water if the shark decides to take a bite, mostly by mistaking us for a seal or a big fish dinner.

In North America prior to 1916, there was never a fear of sharks simply because there had been no documentation of sharks attacking human beings in temperate waters. In 1891 Hermann Oelrichs, a banker/adventurer, even put up a reward for anyone who can document a shark attack in the temperate waters of North America. Everything changed in 1916, detailed in Richard Fernicola’s book entitled “Twelve Days of Terror,” when, in over a span of just 12 days, four people along of the shores of New Jersey were killed by a shark, most likely a bull shark rather than a Great White (a story that inspired Peter Benchley’s book, “Jaws.”)

The idea of a shark repellent was not new. It was suggested way back in 1895. However, serious work on the idea started with the US Navy during World War II when airmen and sailors inevitably find themselves in shark infested waters. The sinking of USS Indianapolis, a destroyer that carried the atomic bomb to the tiny Pacific island of Tinian, by a Japanese torpedo made that need imperative. The mission was so secret then that no SOS signal was transmitted even as the ship sank with over a 1,000 sailors in the water. When they were finally rescued 4 days later, only 316 remained alive, the rest were eaten by sharks.

The idea of a shark repellent was not new. It was suggested way back in 1895. However, serious work on the idea started with the US Navy during World War II when airmen and sailors inevitably find themselves in shark infested waters. The sinking of USS Indianapolis, a destroyer that carried the atomic bomb to the tiny Pacific island of Tinian, by a Japanese torpedo made that need imperative. The mission was so secret then that no SOS signal was transmitted even as the ship sank with over a 1,000 sailors in the water. When they were finally rescued 4 days later, only 316 remained alive, the rest were eaten by sharks.

The Navy developed a shark repellent, called the “Shark Chaser.” It was ineffective, yet given to sailors more for morale to allay fears of sharks rather than as a true protection. Shark research continued after the war through the Office of Naval Research (ONR) through the 1960’s with not much success either.

Eugenie Clark, a world renowned shark expert, discovered in the 70’s that a flat fish in the Red Sea, aptly called Mose’s sole (Pardachirus marmoratus), can repel sharks. Sharks have a powerful bite and when committed to a potential meal, would not likely stop. When the fish is about to be bitten, the shark stops at mid bite and run’s off like a scared rabbit. It was found later on that the flat fish has glands along its sides that secrete a venomous cocktail of peptides and steroidal compounds, presumably not meant to frighten sharks, but to repel/stun organsims as it glides along the sandy bottom of the Red Sea. It is the Mose’s sole’s fast food drive-in! Like our quick trip to McDonald’s for a fish sandwich.

When purified, this 33 amino acid peptide repellent was called pardaxin, a term coined by Naftali Primor, an Israeli scientist funded at the time through ONR, working in one of the laboratories at New York University. As my research team at NYU Medical Center tended to work long hours, Naftali often came by for a short visit at night, the first time to get some of our ‘extra’ mice for his pet snakes. We talked often about sharks, snakes, Israel and Chinese food. During this period, he was able to demonstrate pardaxin’s mechanism of action. This peptide create pore channels through the gill membrane that causes a sudden rush of sodium ions through the gills. Likely, it is perceived by the shark as an ‘unpleasant” or perhaps a painful experience. Naftali used to go out to the fishing port in Montauk Point at the end of Long Island to remove gills from sharks caught by fishermen. It took a day’s hard work to get enough for his research. One night, he came back totally disgusted and exhausted. The cooler was just open for a moment and seagulls rushed to eat all the shark gills he collected. By then my interest in pardaxin got stimulated. Yours truly‘s contribution to shark science was helping him dissect late into the night the opercular cells out of the killifish, Fundulus heteroclitus, to use a model system to validate the concept. Certainly beats hanging around fishing ports for shark gills and fighting off seagulls! He told me one night jokingly that Orientals are the ones with the patience for this kind of work. I just chuckled because I knew he was right!

My real interest was to develop a gadget, a release mechanism that would enable dispersion of pardaxin or pardaxin-like analogues around the person in water upon seeing the shark. Great idea, if we only had enough repellent. I did manage to develop a prototype for the device that still sits on my desk till now with many fond memories. But, back then the cost of synthesizing the active compound and the liability issues (if the person who have the device got bitten) in a litigious society like United States made the project at that time quite daunting.

Dr. Naftali Primor holding a restrained venomous snake( Daboia palaestinae). Its venom is being used for the production of a life saving anti venom.

Naftali eventually returned to Israel, but continues to work on venoms. This time his interest is turned on to new exciting research on the analgesic effects of small peptides from snake venoms. This new concept, called Zep3, is a promising technology for relief of chronic pain and treatment of various skin disorders, such as those caused HSV viruses. This scientific adventure started me on the path of studies on repellents, leading to the development of barnacle and insect repellents called MR08. All these new body of work and long-term friendship started on a chance meeting at the corridor of NYU Medical Center 25 years ago.

There had been continuing work on repellents from many other scientists. That pardaxin also behave like surfactants led to new work on molecules, like SDS (sodium dodecyl sulfate), that can ward off sharks. SDS did not meet the Navy requirement of a non-directional surrounding cloud-type repellent at 100 parts per billion. It would require a barrel full of SDS to ward off sharks around a single person. It is likely useful as directional type repellent where one squirts directly on an oncoming shark. Not likely a viable option for a swimmer in panic. Other products include the Shark Shield, a Navy led research on bag type product with a floats where one climbed inside to avoid being detected by shark. There is also a similar concept of bubbles created around a swimmer to deter sharks. There is always of course the shark cage to hide into. A patent was issued for the Shark Stopper, an acoustic device to ward off sharks. Wet suits with surface patterns to mask the silhouette of a man underwater are also being developed. More promising areas of work these days involve semiochemicals, associated with decaying shark carcasses (Shark Defense Technologies) that act as small molecule messengers that modulate shark behavior.

JFK and the Mercury astronauts

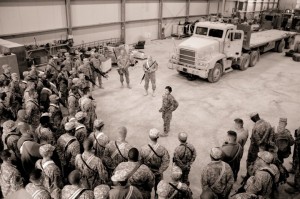

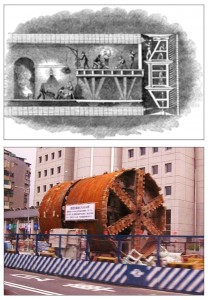

Consider this scenario: America sends a daring young astronaut, the cream of the crop of military pilots (immortalized in the book and movie entitled ‘The Right Stuff’), the best among the best, in a space ship to outer space at a cost of billions of dollars in today’s money; against all odds, the ship survives re-entry and the tiny capsule comes back to Earth, lands in the ocean; the astronaut comes out alive from the tiny space capsule, swims to be rescued and then eaten by a shark in full view of journalist and shown on live television all over the world! This was President John F. Kennedy’s and NASA’s nightmare scenario; hence, the sharpshooters on board the helicopters.

Consider this scenario: America sends a daring young astronaut, the cream of the crop of military pilots (immortalized in the book and movie entitled ‘The Right Stuff’), the best among the best, in a space ship to outer space at a cost of billions of dollars in today’s money; against all odds, the ship survives re-entry and the tiny capsule comes back to Earth, lands in the ocean; the astronaut comes out alive from the tiny space capsule, swims to be rescued and then eaten by a shark in full view of journalist and shown on live television all over the world! This was President John F. Kennedy’s and NASA’s nightmare scenario; hence, the sharpshooters on board the helicopters.

The image of an astronaut being eaten by shark was not out of irrational fear and dark imagination. Prior unmanned space capsules brought of out the water occasionally had embedded shark teeth on the heat shielding tiles. Like all ships of the period, Project Mercury’s Friendship 7 came with standard military survival kit and included a shark repellent device that shoots out of the capsule ahead of splash down.

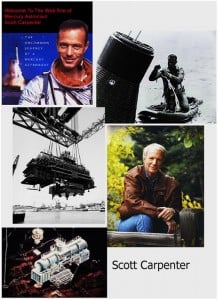

Years after my shark science with Naftali, I reluctantly went with my wife one night to attend a marketing conference in Connecticut, sponsored by Arbonne, a cosmetic company. The after dinner speaker, to my great surprise, was Scott Carpenter, who recounted his days as a Mercury astronaut. In his dinner speech, he related the story of NASA’s preoccupation with sharks. As the NASA-US Navy liaison officer, astronaut Scott Carpenter took the NASA- approved shark repellent device and sent it to the Navy’s shark experts for validation testing. Scott related that as he was preparing to embark on his first space trip, he received a letter from the shark experts essentially saying that “the electronic shark chaser device was interesting with all the lights and sounds, but appeared to be mildly effective against sharks in either the on or off positions!” Later, after the Mercury Mission, Scott became part of the Sealab Program to develop underwater living habitats — the only austronaut who also became an aquanaut.

Years after my shark science with Naftali, I reluctantly went with my wife one night to attend a marketing conference in Connecticut, sponsored by Arbonne, a cosmetic company. The after dinner speaker, to my great surprise, was Scott Carpenter, who recounted his days as a Mercury astronaut. In his dinner speech, he related the story of NASA’s preoccupation with sharks. As the NASA-US Navy liaison officer, astronaut Scott Carpenter took the NASA- approved shark repellent device and sent it to the Navy’s shark experts for validation testing. Scott related that as he was preparing to embark on his first space trip, he received a letter from the shark experts essentially saying that “the electronic shark chaser device was interesting with all the lights and sounds, but appeared to be mildly effective against sharks in either the on or off positions!” Later, after the Mercury Mission, Scott became part of the Sealab Program to develop underwater living habitats — the only austronaut who also became an aquanaut.

As we celebrate John Glenn’s and Scott Carpenter’s 50th anniversaries of their space flights, America should be grateful that JFK’s nightmare of his astronauts being eaten by sharks never came to pass.

The most eloquent sentence in space travel to date was by Scott Carpenter before Friendship 7’s lift-off: “God speed John Glenn”

Jonathan R. Matias

Poseidon Sciences Group

www.poseidonsciences.com [email protected]

Dedicated to my children who are on their own unique adventures.

References:

Lazarovici P, Primor N, Loew LM Purification and Pore Forming Activity of Two Hydrophobic Polypeptides from the Secretion of the Red Sea Moses Sole (Pardachirus marmoratus). J Biol Chem. 1986. 261:16704-167123

Primor N. Pardaxin produces sodium influx in the teleost gill-like opearcular epithelia. J exp Biol. 1983. 105:83094

Primor N. Pharyngeal cavity and the gills are the target organ for the repellent action of pardaxin in shark. Experientia. 1985. 15: 693-695

Primor N, et al. Toxicity to fish, effect on gill ATPase and gill ultrastructural changes induced by Pardachirus secretion and its derived toxin pardaxin. J exp Biol. 1980. 211:33-43

Sisneros JA,Nelson DR. Surfactants as chemical shark repellents: past, present and future. Environmental Biology of Fishes. 2001. 60:117-129

http://au.news.yahoo.com/thewest/a/-/breaking/12848556/experts-work-on-wetsuit-to-outwit-sharks/

http://news.yahoo.com/john-glenn-reunites-50-old-mercury-team-022029804.html

http://www.scottcarpenter.com/sealab.htm

http://www.collectspace.com/ubb/Forum29/HTML/000375.html

http://sharkdefense.com/Repellents/repellents.html

http://the.honoluluadvertiser.com/article/2005/Aug/22/ln/FP508220336.html

http://onlineissues.wherewhenhow.com/article/Dive+Training+Shark+Repellent/866010/85272/article.html

http://www.mach25media.com/bookspacious.html

| BibTex | EndNote | RefWorks Download | ||