Despite the recent spectacular scientific achievement of DARPA (US Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency) on a hypersonic glider traveling at 13,000 miles per hour, American innovation, like this Mach 20 glider, is on a downward path towards unknown depths, with profound ramifications to our economic and political status among nations. We all know intuitively that the declining trend exists and I am not sure there is a way to reverse that in such a complicated world we live in today. In my life experience as an American scientists and a former immigrant, I can see it as clearly as the sun sets behind midtown Manhattan from across the East River in Gantry Park.

Often, I sit on the bench at Gantry Plaza State Park waiting for sunset, mostly alone or at rare times with my kids or friends. Just recently I began thinking about my years through graduate school, work, science and the economy. These thoughts came about after a friend sent me a link to an MSNBC interview with Michael Greenstone, an MIT economist heading the Hamilton Project, on the subject of the Innovation Gap. It is definitely worth taking time to see the video before reading the rest of my blog. Here it is http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/21134540/vp/44041044#44038620

Often, I sit on the bench at Gantry Plaza State Park waiting for sunset, mostly alone or at rare times with my kids or friends. Just recently I began thinking about my years through graduate school, work, science and the economy. These thoughts came about after a friend sent me a link to an MSNBC interview with Michael Greenstone, an MIT economist heading the Hamilton Project, on the subject of the Innovation Gap. It is definitely worth taking time to see the video before reading the rest of my blog. Here it is http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/21134540/vp/44041044#44038620

My career spanned the period from the height of American innovation of the 70’s and 80’s to its post-millennium decline. Why the decline? There are already many reasons that pundits, strategists, economists, professors and politicians came up with and you can read them elsewhere. But, it’s not just because of the rise of China and India as economic powerhouses. It is not just the decline in American knowhow or enthusiasm for the sciences. And it is not just outsourcing. It’s all of these. Most of all it is about the human element–the scientists.

Sitting in Gantry Park at sunset is like a metaphor of the waning American supremacy in science and technology. American innovation is spectacular in its achievements, like the burst of light of the waning sun behind the majestic skyscrapers of Manhattan, slowly fading away to darkness.

Just to digress for a minute, what’s so special about Gantry Park anyway, you may ask? I think of it as one of the most beautiful small parks in New York City, with the breathtaking view of Manhattan, especially at dusk. It is at the waterfront in Hunter’s Point on what used to be an industrial/ warehouse district no one wanted to be  caught walking at night years ago; a place to be avoided then, but not anymore. Once the site of the Pepsi bottling plant, whose sign still remains today as a relic of the past, this waterfront area in the 1920’s serviced rail cars coming from Manhattan and New Jersey to supply the industrialized Long Island City in the NYC borough of Queens. Gantry refers to cranes that lift objects by hoists that move horizontally. Back in the heyday of American industrial might, rail cars were lifted off barges, moved on to rail tracks and hooked on to trains that crisscrossed Long Island. With the decline of American industries and the pre-eminence of trucking systems, the gantries ceased to serve its purpose and the machines became silent, another testimony to the doomed manufacturing industry. One can still see the original rail road tracks in between the manicured gardens.

caught walking at night years ago; a place to be avoided then, but not anymore. Once the site of the Pepsi bottling plant, whose sign still remains today as a relic of the past, this waterfront area in the 1920’s serviced rail cars coming from Manhattan and New Jersey to supply the industrialized Long Island City in the NYC borough of Queens. Gantry refers to cranes that lift objects by hoists that move horizontally. Back in the heyday of American industrial might, rail cars were lifted off barges, moved on to rail tracks and hooked on to trains that crisscrossed Long Island. With the decline of American industries and the pre-eminence of trucking systems, the gantries ceased to serve its purpose and the machines became silent, another testimony to the doomed manufacturing industry. One can still see the original rail road tracks in between the manicured gardens.

Now, it is gentrified, with bustling new businesses and pricey condominium buildings mushrooming around the park. It is one of the those truly wonderful little known places in New York, just a subway stop in Queens Borough on the #7 subway train from Manhattan’s Grand Central Station-42nd Street. I go there because it is a quiet place to contemplate, work and just simply do nothing or go fishing (I have yet to try that). As I sit by the fishing pier, I can see where I had been. From my beginnings as a research intern at Goldwater Memorial Hospital on Roosevelt Island on the right of the East River, through my days in graduate school at New York University, my work at Orentreich Foundation on 72nd Street, my old labs leased by the Foundation at NYU Medical Center Public Health building on 29th Street and the Metro North trains I took from Grand Central Station– all laid out for me just across the East River.

In a way, standing there on that pier gives me a quick view of where I had been. Here I share an anecdote about the multibillionaire, Harry Helmsley, among the great real estate magnates of his time; back in the 1970’s when he used to stand on a waterfront building in New Jersey facing Manhattan. When asked why he often have luncheons on top of this building. He replied (from memory), “I am old now. I cannot understand the spreadsheets of real estate properties my accountants carry around. Standing here, I can see all of Manhattan and I do my own accounting. I own those buildings there, there and there. And I can see the buildings I would like to buy over there and there. Here I take stock of where I had been, what I have and where I am going.” In a way, standing on the pier at Gantry Park also shows me where I had been, though not necessarily where my life is heading at the moment.

Having digressed enough, I would like to tell you what I think about how the decline of American innovation came about.

In the 70’s and 80’s and certainly even decades before, American innovation in computers, engineering, chemistry and practically all scientific pursuits were in a frenzy. American technology dominated the world, from soft drinks to blue jeans. That was also a time when young men and women from foreign lands flocked to American universities to continue graduate school. That was a time when foremost in the mind among foreign students, who tend to work harder than most, was the dread of having to go back where they came from, where political instabilities, economic issues and lack of opportunities persisted. Coming back to their home countries was not on their priority list, reaching the American dream was. That means being sponsored by a company and making big bucks. I know that for a fact as I had sponsored many during that period. That also was a time when American businesses need more scientists and the steady flow of foreign student filled that gap. And, talented scientists flocked into America through working visas.

In the 1980’s China was just experimenting on private enterprise. Having visited China in those days, I have seen the change; from the early days with people wearing Chairman Mao style jackets and avoiding contact with Americans to a time when local Chinese students would go out of their way to meet with me just to practice their English. (That was also a time when I was courageous in haggling with a street merchant for a pair of shoes that I know was worth $75 in NY, then coming back to the hotel proudly telling the concierge that I got it for $4 and only deflated when he told me I was cheated—it was only $2 for the locals. I knew then something was very wrong).

It was the 1990’s when things began to change. China opened its doors to manufacturing for overseas markets and India slowly made strategic changes in its business laws. Exports brought wealth and China opened a hybrid enterprise system allowing private ownership. American and European companies saw the opportunity for cheaper good to be manufactured, increasing their profitability and dooming their own domestic manufacturing industries. More important, foreign students and foreign workers began to have a change of attitude about coming home. It is not simply being homesick that drove them back. Certainly they have the economic capacity to come home for frequent visits. It was the lure of starting a business in their home countries where economic opportunities began to be rosier than struggling in America. For these young men and women, it was riskier but the potential opportunities outstrip what they can get here.

I know this because I was once one of them. In 1995, I came back to the old country, started some businesses, did research at a cost of 1/10th it would had I stayed in America. Though political issues had made me return to New York in 2000, the experience was profound, memorable and productive. I was able to accomplish much more in that 5 years than I could have possibly done in NYC in 20 years. The 1990’s also saw countries adjusting to the new-found wealth. By the turn of the century, opportunities abounded in Asia. It was no longer a risky experiment for foreign scientists from America to come home. The infrastructure, though imperfect, was there, waiting for the young scientists/entrepreneur from America. American knowhow, learned from years of study and hard work are being snapped up by companies in foreign soil. Is there anything wrong with that? Absolutely not, as long as they are not bringing patented ideas. And even so, most of those countries are not places American inventors filed their patents anyway and therefore free for the taking and/or improvements.

America is hemorrhaging its talents not just from reverse migration. American talents from those born here are also being lured by foreign companies and governments with higher wages, better scientific support and a better life style than they could ever imagine at home. Just simply take the case of Singapore, whose expat communities are bursting at the seams. American innovations are being sucked out of the country year after year. You will see great innovations coming out of Asia in the next decade, innovations that would have originated from America had we been able to keep our scientists happier at home.

These thoughts are from my own personal experiences. Can I support this point of view? Absolutely!

The backbone of a modern economy is innovation. In the days of the Spanish, the British and the Portuguese empires, economic wealth came from conquest of new lands and people. Modern economies, such as the ‘American Empire,’ is built solely in innovation; not the military innovations whose proprietary ownership is often fleeting. Take the case of the US stealth fighter shot down in Serbia and ended up being reversed engineered by the Chinese who now have stealth technology of their own. Outsourcing in history is best exemplified by the Roman Empire, whose lack of foresight and need to save money on its military outsourced the defense of its borders to ‘barbarians.’ The Goths, Visigoths and others eventually turned on the Empire, emptying Rome of its 1 million inhabitants down to the size of Google’s workforce of 30,000 by simply destroying its greatest innovation—the Roman aqueducts that brought freshwater to the city.

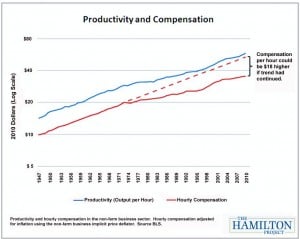

The Hamilton Project demonstrated that the loss of America’s innovative edge translated to American workers losing 51% of the value of the dollar compared to the  1970’s. This loss of purchasing power was made up by credit and eventually led up to our current economic crisis. There is no direct way to show how innovation’s decline affects our economy. However, the 2009 article by Vivek Wadha in YaleGlobal served to highlight the impact of migrant workers, foreign students and immigrants on the American economy. A most telling part of the article described an adhoc question he posed on Indian techies at a conference on who wanted to return home. Fifty percent raised their hand. Had I asked the same question in the 1980’s, I would had been lucky to get one! It is really worth reading his article entitled “Is the US brain drain on the horizon? Immigrants now see better prospects back home” (see link below).

1970’s. This loss of purchasing power was made up by credit and eventually led up to our current economic crisis. There is no direct way to show how innovation’s decline affects our economy. However, the 2009 article by Vivek Wadha in YaleGlobal served to highlight the impact of migrant workers, foreign students and immigrants on the American economy. A most telling part of the article described an adhoc question he posed on Indian techies at a conference on who wanted to return home. Fifty percent raised their hand. Had I asked the same question in the 1980’s, I would had been lucky to get one! It is really worth reading his article entitled “Is the US brain drain on the horizon? Immigrants now see better prospects back home” (see link below).

Considering that the Chinese and Indian nationalities in the US represent only 3% of the population, over 25% of all patents have ethnic Chinese and Indians listed as inventors.

Vivek Wadha writes:

In 2006, immigrants contributed to 72 percent of the total patent filings at Qualcomm, 65 percent at Merck, and 60 percent at Cisco Systems. And contrary to claims that immigrant patent-filers crowd out US-born researchers, emerging research is increasingly showing that immigrants actually tend to boost patent output by their US born colleagues. These immigrant patent-filers emerged from the US university system, where foreigners now dominate the advance degree seeking ranks in science, technology, engineering and mathematical disciplines. For example, during the 2004–2005 academic year, roughly 60 percent of engineering Ph.D. students and 40 percent of Master’s students were foreign nationals. (We don’t know for certain that those who have been leaving are patent-filers but anecdotal evidence suggests this to be the case).

Beyond intellectual contributions, Chinese and Indian immigrants have been key entrepreneurial drivers in the US. According to another survey we conducted, one-quarter of all technology companies in the US have at least one founder who is a Chinese or Indian immigrant. The concentration is even heavier in certain key industries such as semiconductors and enterprise software. Based on this data, we calculated that in 2005, immigrant-founded tech companies generated $52 billion in revenue nationwide and employed 450,000 workers. This revenue total bridges multiple multi-billion dollar sectors including semiconductors, Internet, software and networking.

…. the Rising East will continue to pull in its fair share of future science and technology rock stars who may build the next Google or Microsoft in Gujarat or Mumbai.

That immigrant-founded tech companies employed 450,000 people with a $52 billion in revenue is awesome to contemplate. And if 50% of them returned home to their own countries, that’s an economic loss that will never be recovered.

The barbarians are at our gates and they are tearing down our aqueducts. What to do?

All is not lost of course. There had been so many suggestion put forth by strategic thinkers. They range from improving educational opportunities, inviting more foreign techies on H1 visa, providing better business opportunities, relaxing the immigration hurdles for scientists. All these require a bouncing economy and political will, both simply lacking in our current domestic environment. Even if those were to be implemented now it is unlikely that the tide will reverse since other countries can offer much more. And Congress has to debate on that for a while if they ever get to it, unless of course they are distracted by something else like elections or the debt ceiling.

The answer is through private initiatives, backed by government immigration reforms specifically tailored for inventors. Here is what I thought of at Gantry Park (I certainly had a lot of free time then):

1. Have a Gates Foundation type of initiative where a fund is created to entice potentially lucrative inventions from overseas. Bill Gates can easily do this with his own money besides creating challenge funds for the best ecofriendly toilet for the third world. (I think toilets are also important. But as one of the great American inventors, it’s time for him to put in a little for his fledgling inventor colleagues of the new generation). We have enough billionaires here in the US and each can donate a million or two to this fund if Gates is preoccupied with toilets. Hey, that’s just your annual budget for fuel for your private jet. Time to kick in some for your country. I would like to call this The Great American Enterprise Fund (GAEF) and a billion $ should just about do it.

2. Winning ideas from anywhere in the world get evaluated by the private sector; not some academics who likely have not made a dollar on his own. Many great inventions were made in the dining room table or the garage—take the case of Sergey Brin and Larry Page of Google. Fellow inventors and business people can make the winning technologies much better than any government or academic-led initiative.

3. Have the winning invention patented in the US and licensed to an American company. With few exceptions, inventors typically make lousy businessmen anyway (me included in that group).

4. If the invention makes X amount of money or employs X number of Americans, give the guy or gal (have to be politically correct here) prize money above and beyond the license for the technology. If he/she is foreign born, give him/her a fast track to citizenship and let him/her invent some more right here in America.

5. What does the donor get? Besides the usual tax write off, whoever invests in GAEF has first option to commercialize the new invention (provided the inventor agrees) before anyone else does and the unique opportunity to feel good about being an instrument in reversing this innovation gap.

For now, that’s all I thought about. Perhaps, someone already have this idea before and just did not know about it. Let me know.

I did not want to miss this sunset because the Gantry Park locals say such a view happens only once a year when the sun comes down at the right angle on 42nd Street. My lucky day!

I did not want to miss this sunset because the Gantry Park locals say such a view happens only once a year when the sun comes down at the right angle on 42nd Street. My lucky day!

Any better ideas or have something to add, just send me a note (use subject heading GAEF) on my email ([email protected]) or send your comments here.

Jonathan R. Matias, Chief Science Officer

Poseidon Sciences www.poseidonsciences.com

PS:

This blog is dedicated to my colleagues who loved inventing: Jason, Mike, Kosta, George, Naftali, Ernie, Saudha, Avelin, Aras, Tim, Coleen, just to name a few.

References:

http://www.qchron.com/news/western/article_5f2a6db9-2e05-5f0d-8c5c-34993b652151.html

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gantry_crane

http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/21134540/vp/44041044#44038620

http://www.brookings.edu/opinions/2011/0805_jobs_greenstone_looney.aspx